Lesson Plan: José Olivarez's "Mexican Heaven"

& some thoughts on windows, glass doors, & mirrors in literature

Can a poem be a block party? Can a poem be a street festival? Can a poem be a city you love with the foods you love and the people you love?

At the beginning of my poetry unit, I often ask students as a conversation-starter: What can’t a poem be?

I project this question on the board1 and ask students to write their responses in their notebooks for a minute. Generally, I use a timer (you can insert videos from YouTube into Google Slides, though recently, this has gotten trickier; if your school’s safety settings prevent integration of videos, you can open a new tab and play the timer) to help keep things moving.

Then, after their independent writing time, I ask students to turn and talk to a partner. In pre-COVID times, I would arrange student desks to facilitate this, in groups of 2-4. During our ongoing pandemic, I ask students to turn to the right or left to whoever is closest to them. I set another timer for 2-3 minutes and I circulate the room, walking around listening to their conversations, while keeping my interruptions to a minimum.

When I hear someone say something interesting in these small (3-4 students) or partner (2) groups—especially if it is a student who normally does not raise their hand to share—I praise them and ask if they would be interested in sharing with the whole group. I call this warm-calling, as opposed to the (too common, I think) educational practice of cold-calling.

Cold-calling—the practice of calling on students to respond to a question without offering time to prepare—disadvantages more introverted students, folks who take longer to process their thoughts into speech, and those who are neurodivergent: since I personally fall into all three categories, I try to make my classroom more equitable by eliminating cold-calling altogether.

I am sure someone else has already trademarked the term “warm-calling,” but for me, it simply is what I named my alternative to cold-calling when I was a student teacher. Warm-calling—allowing students to independently process their thoughts and/or share with a small group or partner, and then safely asking the student to share with the whole group—helps bring out voices that you otherwise would not hear in the room. Those voices are important and they too often go unheard.

Back to my initial question: What can’t a poem be? Wow, the responses to this one are always incredible. A poem can’t be a sandwich with stuff falling off the ends! A poem can’t be a math equation! A poem can’t be a story (oooh!)! A poem can’t be a ballerina swimming the Pacific Ocean in a rainbow leotard!

Of course, then we talk about all the ways a poem could be all the things we said a poem couldn’t. It’s an incredible amount of fun, and I encourage you to consider this as a conversation opener for your poetry unit or one of your “Do Now’s2” on the board.

It is helpful to have had this conversation—although to be clear, not at all strictly required—by the time we reach José Olivarez’s expansive and gorgeous “Mexican Heaven” because Olivarez’s poem answers resoundingly yes to the questions with which I opened this newsletter: YES! it is a block party! a street festival! a city! the foods you love! the people you love! Olivarez’s poem is all that and it is one of two poems3 that I teach which never fails to engage students:

"A Mexican Dreams of Heaven" all of the Mexicans sneak into heaven. St. Peter has their name on the list, but none of the Mexicans have trusted a list since Ronald Reagan was President. * St. Peter is a Mexican named Pedro, but he’s not a saint. Pedro waits at the gate with a shot of tequila to welcome all the Mexicans to heaven, but he gets drunk & forgets about the list. all the Mexicans walk into heaven, even our no good cousins who only go to church for baptisms & funerals. * it turns out God is one of those religious Mexicans who doesn’t drink or smoke weed, so all the Mexicans in heaven party in the basement while God reads the bible & thumbs a rosary. God threatens to kick all the Mexicans out of heaven if they don’t stop con las pendejadas, so the Mexicans drink more discreetly. they smoke outside where God won’t smell the weed. God pretends the Mexicans are reformed. hallelujah. this cycle repeats once a month. amen. * Jesus has a tattoo of La Virgen De Guadalupe covering his back. turns out he’s your cousin Jesus from the block. turns out he gets reincarnated every day & no one on Earth cares all that much. * all the Mexican women refuse to cook or clean or raise the kids or pay bills or make the bed or drive your bum ass to work or do anything except watch their novelas, so heaven is gross. the rats are fat as roosters & the men die of starvation. * there are white people in heaven, too. they build condos across the street & ask the Mexicans to speak English. i’m just kidding. there are no white people in heaven. * tamales. tacos. tostadas. tortas. pozole. sopes. huaraches. menudo. horchata. jamaica. limonada. agua. * St. Peter lets Mexicans into heaven but only to work in the kitchens. A Mexican dishwasher polishes the crystal, smells the meals, & hears the music through the swinging doors. they dream of another heaven, one they might be allowed in if only they work hard enough. José Olivarez - The Adroit Journal: Issue 24

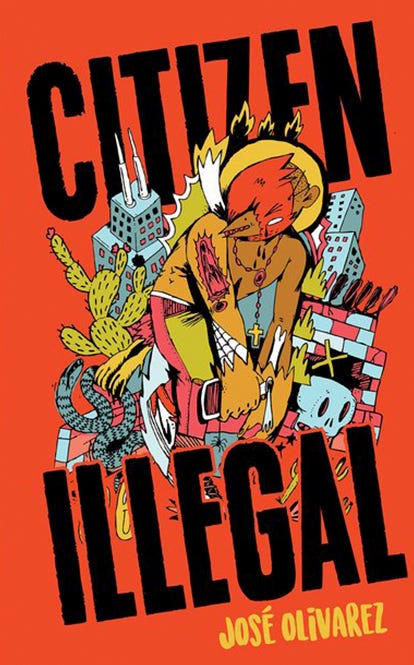

I chose this poem from Olivarez’s brilliant debut collection, Citizen Illegal published in 2018 by Haymarket Books (available here), when I was working with predominantly white students in my honors 9th grade English class and predominantly Latinx, first-generation immigrant students in my ELD (English Language Development) class. When I choose texts for my classroom, it is often with the words of Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat foremost in mind: “Write for the twelve-year-old girl who is looking at a mirror and at a window.” Children, she argues, need both mirrors—reflections of themselves—and windows—views into other realities and identities—in the literature they read and I strongly agree.

Olivarez’s poem does such a fantastic job interrogating mirrors and windows while providing them—for so many of my immigrant students, and myself, we find ourselves and our families, our communities, in it. And for my non-immigrant white students, there is some discomfort—not to be confused with lack of safety—and that discomfort is healthy: when we look at white supremacy, we as white people should feel uncomfortable. It is a sign of our humanity and hopefully, of our willingness to change inequitable systems, to acknowledge the racism which benefits us and to divest from it. The classroom is a place of safety, and safety means sitting with discomfort and asking hard questions. Olivarez’s rollicking and rambunctious poem is a great place to start or continue these conversations.

We begin by first reading the poem out loud. For any poem, I generally have us read it out loud 2-3 times. I often read it first, to clear up any pronunciation issues—though I also own when I am uncertain as to how to pronounce a word and try to model how to normalize making mistakes regarding pronunciation. Many students—myself included—may have learned a word by reading and have never heard it spoken out loud. Then, I have a student volunteer (or two) read the poem. Next, we listen to José read the poem out loud at a poetry slam; linked here is my favorite version of José’s reading of the poem.

[Above Image Description: Screenshot from YouTube video of José Olivarez reading. José is standing at a wooden podium with a mic, right arm outstretched, and wearing glasses and a black baseball cap. His sweater is light pink and contains an image of La Virgen de Guadalupe at the center.]

Watching students watch this video is such a treat, especially if this is the first poem you teach in your unit. So many of them come in with expectations that poetry is dead and dusty. This poem is exuberant and so alive with what the speaker loves. It defies what many students will expect out of a poetry unit and it is delightful to see it happen.

Following the video, I ask students to talk with their partners or small groups about how listening and seeing the poem performed changed their interpretation of the poem from when we read it aloud. This is a great technique for spoken word and/or slam poetry in general: share the written text first and then have students listen/see the performance.

We then get into the close-reading of the poem and I ask students to annotate their copies, in response to the following questions:

What are the repetitions? Or, what words or images are repeated, if any?

What are the similarities? Or, what images or words feel like they create a pattern or belong in the same category?

What are the contradictions? Or, how does the poet set up expectations and then break them?

What connotations are we finding?

Is the author and the speaker the same person?

What are the goals of the speaker of the poem?

You may note that the above questions are helpful for almost any poem you teach and they stem from the close-reading methods I discussed at length in yesterday’s newsletter (“Two Lessons: Murder and Theft”).

Generally, I do not try to hit all of these questions in one class period. I will choose a few depending on where the conversation is heading, give students some independent time to annotate on their own, followed by time to discuss in small groups or with partners, and ending with whole class discussion. I do want to include here a few helpful, guiding questions for this poem in particular, that could lead to deeper discussion:

How does Olivarez use his references to God and St. Peter to set up and defy our expectations of what this poem will communicate?

What stereotypes about Mexican culture does Olivarez describe and how does he choose to subvert (undermine their power) them through his writing and/or his delivery of the poem?

How does Olivarez use comedy in this poem to deliver uncomfortable observations of reality? In particular, what is the effect of his lines “i’m just kidding. there are no / white people in heaven4.”?

Why do you think Olivarez includes the penultimate (second-to-last) stanza entirely dedicated to food? How does it fit in, or not, with the rest of the poem?

How does that final stanza speak to the message of the entire poem and what does it ultimately reveal about the speaker’s view of power structures in the United States? What does the contradiction of including “hard work” in “heaven” reveal?

What, if anything other than itself, does “Mexican Heaven” represent or symbolize?

[Above Image Description: Cover art for José Olivarez’s book Citizen Illegal: organge-red background with words CITIZEN ILLEGAL in black all caps and name José Olivarez in smaller yellow all caps. Intricate drawing by artist Sentrock, featuring a bird-like figure wearing a rosary, buildings, a cactus, a snake, and a skull. Link to artist’s website here: https://sentrock.com/ ]

Again, we do not hit all of these questions and I am much more in favor of, whenever possible, letting students take the reins of the conversation and direct it to where they want to go. And oh gosh, do they want to go places with this poem! This is just one of those poems that you read together as a class and you will have students asking if they can be late to their next class to keep talking about it.

At this stage in the poetry unit, I am not normally asking students to do any other kind of written assessment on the poem besides annotation. In a later newsletter, I will talk about how I teach thesis statements and thematic statements. I think poems are great tools for teaching students how to do those well.

But, truly, sometimes, I just want students to love a poem. Really. That is the goal. Let a poem sweep you up. Olivarez’s “Mexican Heaven” has the secret sauce that does that. If you need your Common Core Standards for this lesson, that’s real and here they are:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language evokes a sense of time and place; how it sets a formal or informal tone).CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.1.C

Propel conversations by posing and responding to questions that relate the current discussion to broader themes or larger ideas; actively incorporate others into the discussion; and clarify, verify, or challenge ideas and conclusions.

Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors: Some Endnotes on the Unbearable Whiteness of the High School English Classroom Curriculum

Danticat’s words about mirrors and windows, which I mentioned earlier, echo those of Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, a foundational researcher in multicultural children’s literature:

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created and recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.”

Students need windows and sliding glass doors and mirrors. What unfortunately most often happens in the high school English classroom is that white students receive an excess of mirrors with few windows and that students of color are constantly looking out windows, never seeing themselves, in the texts we read. And in such a reality, there is limited possibility for sliding glass doors, for stepping into others’ realities, and garnering the critical empathy that is such an important goal in education.

There are limits to empathy, yes, and thus, I add “critical” because reading about another’s story does not entitle you to claim that lived experience. However, the need for careful listening, for nuance, for compassion, for solidarity, for an acceptance that our destinies on this shared planet are inextricably bound with one another’s—these are, I argue, the stakes of teaching English.

And when your literary canon is dusty and you are regularly feeding all your students a steady diet of whatever the presses churned out pre-1960’s US by white men, then you are teaching white male students that they are the center of the universe and everyone else that they are the others. Students of color need to see themselves as the main characters and white students need to see people of color as the main characters, too.

Olivarez’s poem is just one text out of so many that helps provide the necessary windows, sliding glass doors, and mirrors that students need. It is, I think, up to us as English teachers to not continue to perpetuate white supremacist practices in our classrooms and this includes having a white-majority syllabus. If you think that students are “missing out” when their curriculum becomes more inclusive and diverse, I encourage you to deeply interrogate that thought.

And then, I encourage you to read some more poetry. It’s not broccoli, but it is a sandwich with stuff falling off the ends. We could all use a little more of that.

What I’m Reading: Too much at once! I continue to re-read excerpts of Avni Vyas’s Little God for my eventually to be finished review of her brilliant book. And about a half-dozen other books, including book #34 of the Animorphs series. It’s a Cassie-narrated one and she’s a fave.

What I’m Listening To: The quiet of the house . . . too quiet . . . what are the cats plotting?

What I’m Watching: In case you thought only trash television was streaming in my home (I love you terrible Hallmark movies! I love you Real Housewives!), happy to report I am now watching the third season of Never Have I Ever, which is gold-tier TV.

What I’m Feeling: Nervous about starting my new job tomorrow!

What Boba Flavor I’m Currently Craving: Honey Oolong Milk with Lavender (I’ve never had this exact flavor; I just think it would be nice.)

Note to self to do a whole newsletter on how I use Google Slides to prepare my lessons, ensuring that: 1. I save time I would otherwise be using to write the material on the board; 2. I organize my lessons towards an end goal via Slides in a way that keeps things clear for me; and 3. it ensures that my students are receiving any information that I share both verbally and visually. Also, a fourth (and not insignificant) reason: I have a lot of fun designing my Slides. It brings me joy. If it does not do that for you, don’t waste your time adding gifs and daydreaming color schemes; it does for me and so I make time for it.

A “Do Now” is a writing prompt that is on the board when students enter the classroom. Students enter the room and as the title states, they do it now: as in, they immediately take out their notebooks and respond to the prompt. I used this regularly during my first couple of years of teaching because it is an excellent routine to help students get settled into class and afforded me a couple of minutes to get myself ready to begin teaching. I found it much more difficult to consistently implement when I moved to a school that had 37-minute class periods, but would still use it on occasion for my 57-minute periods. Students will always need more writing practice than you could possibly grade in great detail and these “Do Now’s” provide a simple and effective way to get it. (Also, sidenote: I never called them “Do Now’s,” but I know a lot of teachers use this term, so I figured I would use it as shorthand here.)

The other is Chen Chen’s “I Invite My Parents to a Dinner Party,” which I’ll discuss in a later newsletter and is linked here for your reading enjoyment: https://poets.org/poem/i-invite-my-parents-dinner-party

This is quite possibly one of my favorite lines of poetry ever and also, the classroom regularly erupts into laughter and “Oh snap!”’s at this moment. A 10/10 poetry moment.

not a teacher of course but this still blew my mind