Community-Building and Expectation/Boundary Setting

I like to start the school-year off with a little light murder and theft.

First, though, some thoughts on classroom management1 because it is relevant to how I present these activities: early on in my teaching career, it was easy to encounter the fallacy of believing you have to intimidate students to obtain their “respect.” Reminder that whatever “respect” you receive through intimidation is actually fear. Some teachers enjoy policing their classroom and believe that students need a little “healthy” fear to learn. Reminder that frightening children is not “healthy” and that compulsion is best examined in therapy2, not enacted in one’s job as a teacher.

Regardless, hovering a little over 5 feet and with a voice so soft my teaching coach recommended I wear a microphone during my first year, I was never going to intimidate students, even if that had been a goal of mine (it wasn’t). How to capture their attention, then, when so many (fellow teachers!) encouraged teachers to be stern, gruff, and downright intimidating on their first week? Don’t be nice! Don’t give them any wiggle room! Don’t even smile! These, and variations, were things I was told to not do during my first week.

I’ve tried being a strict disciplinarian. Here is one great thing about students: they will call you out on your bullshit. They certainly did for me and I’m grateful I was aware of this by the time I entered the classroom full-time at the age of 26. In my years of teaching practice before this, I definitely struggled and often failed to figure out “classroom management.” The majority of those failures came from trying to be someone who I’m not: someone who doesn’t allow room for mistakes, not only academic but relational. We all need a little grace.

What I do instead: I set clear expectations and boundaries. I stress our relationship to each other: my humanity recognizing theirs and vice versa and with each other. I do not assume anything I have not clearly spelled out for students—in a variety of ways: verbal, written on the board, and given to them, electronically or on paper. This system is not perfect—no system is—and it does not produce robots: might I suggest working in a job without people if that is what you are looking for? Our students are human beings just as we, their teachers, are, and by transparently having these discussions with them, I have been consistently able to create an imperfect, but ultimately safe and brave space as our classroom community.

Murder Mystery, or How to Close-Read

This brings us back to murder and theft. I don’t actually get into these weighty talks about what community means and the creation of norms on the first day. I know that these conversations are happening—either directly or vaguely—in other classrooms, along with all the nuts and bolts. I save that for day two at the earliest. I wait until my students are seated (I do let them sit where they want on day one—barring COVID-19 restrictions—because this gives me initial insight into students’ personalities and friendships right from the start) and then, I say:

“Welcome. There has been a murder!”

If you’re thinking this is unhinged, you are correct. If you are wondering if this immediately grabs students’ attention and makes them listen, the answer is yes. Call it “classroom management” if you’d like. For me, it simply is what works.

We immediately get into the work we are going to do this year: close-reading a text. I set it up this way so that when we do go over our classroom norms and expectations together, they know why they are signing up to be cooperative and caring community members: we have academic goals together and it is going to look like what we are doing on day one—which is, I have to say, a lot of fun.

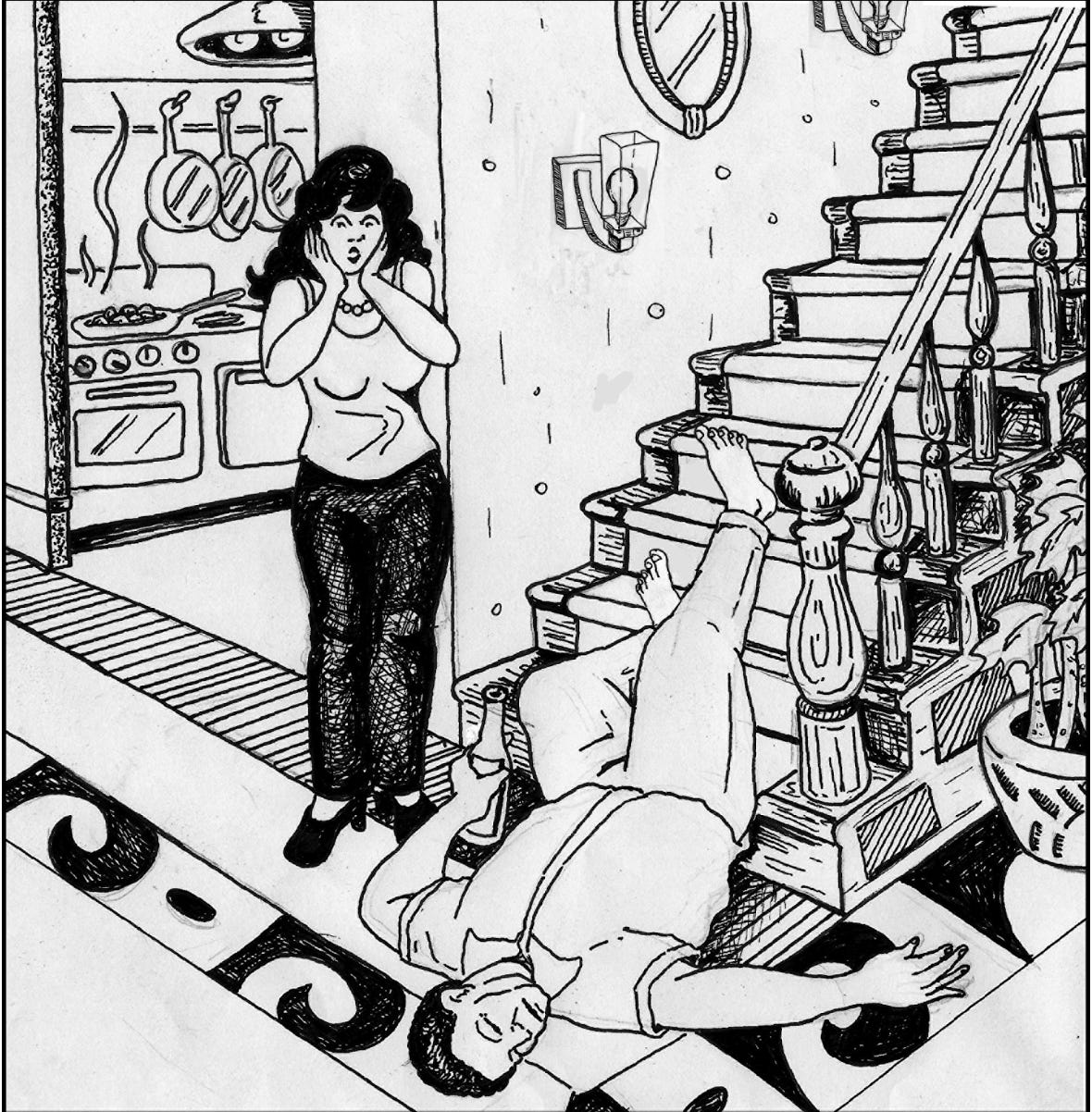

What I’m going to share with you is what was shared with me in my graduate course at Stanford by two of my favorite professors there: Sarah Levine and Jeremy Glazer. I honestly do not know who originally made this resource, despite meticulously scouring the internet, and so if anyone does know, please comment below, so that I can give them proper credit3. After announcing the murder, I give students4 this handout with the following image and text below:

Spill or Kill?

On the evening of Feb. 13, Laura got into yet another fight with her husband, Arthur. She went running out of the house to a party that her friend Collette was hosting.

She sat for a while at the party, talking with Collette. She talked about her frustration with Arthur, and especially about his drunkenness. “He gets drunk every Saturday night, and he trashes the house! I spend all of Sunday cleaning up after him – broken dishes, punched in walls! And sometimes he throws up, and blacks out. I’m at the end of my rope!”

Laura left the party shortly before 1 am. Before she left, she invited Collette back to her place to watch a movie. Collette at first declined, because she had a lot of cleaning up to do. But Laura pleaded with her, offering to drive Collette and saying, “I just don’t want to be alone with him.” She was near tears. Collette agreed to go to Laura’s, but she chose to drive in her own car.

Collette got to Laura’s home about ten minutes after Laura. When she rang the doorbell, she heard footsteps, and then a scream. Laura wrenched open the door and stuttered, pointing to the stairs, “Arthur! He’s dead! He’s – did he – he slipped and fell on the stairs. He was coming down for another drink--he still had the glass in his hand – oh no, oh my God, he’s dead! What should I do?”

The autopsy concluded that Arthur had died from a wound on the head and confirmed the fact that he'd been drunk.

Generally, I read this out loud—in a ridiculous voice if I’m feeling particularly inspired, but I promise it is not necessary and you should only do that if it feels both fun and authentic to you—and occasionally ask for student volunteers to read parts of it for the whole class. Then, I divide students into small groups (3-5 students) and give them their task: solve the murder. Was it a spill or kill?

I explain from the start that their argument needs to include at least two pieces of specific evidence from the text, both the words and the image, and that they have to make it clear why that evidence supports their claim. I say and have printed on the board via my handy slides, “Your claim needs a ‘because.’ What follows the ‘because’ must justify what comes before it. Include two pieces of specific evidence and explain why the evidence proves your argument.”

Then, I leave them to it and the discussions that follow are fascinating! I circulate the room and make knowing eyebrows, but my job is to get out of the way and not offer any hints. I will, for good measure, often play some spooky music in the background.

In case you’re wondering—and to the chagrin of my students—there is no one correct answer to this mystery. There are, however, many remarkable (and honestly, a little unsettling) claims for students to create. I won’t share my personal claim on it (though I will share what one student told me: which is that an open flame is a great way to make blood stained on a metal surface invisible 😲 . . . take that as you will), but I encourage you to join in on the fun.

Every classroom community is different, so the amount of time this will take will vary, but generally, I’d recommend setting aside two class periods of at least 40 minutes each: one class period for students to do the investigative work and another for them to prepare and present their claims.

Every time I have done this, it has been an overwhelming success. There are some lessons that really are so hit or miss. Some variable will set something off. This is as close to a perfect win I have gotten each time: students are engaged and active and eager to share.

After we debrief on the activity, I explain how this detective work is precisely what we do when we close-read a literary text: we look at patterns and create claims from those patterns. In describing the patterns, we are not just summarizing what exists, but instead using this examination to prove a claim. I remind students that when they were trying to prove their arguments, they did not merely paraphrase the story or put the details in other words: no, they showed specifically how those details led to their claims. That is what we do when we close-read.

Before moving on to the next activities, I want to share the Common Core English Language Arts5 standards that this lesson hits:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1

Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

Casually Stealing a Few Items on the Bus, or How to Close-Read a Poem

After the dust has settled a bit on our brief encounter with murder, I go into another favorite activity, sadly one I had to shelve during COVID-19 because I did not want students to handle items in common. However, now that I have had a summer to reflect, there is a way to do this and keep students safe. I will first describe how I originally implemented this lesson and then, I will provide a workaround for how to safely carry out this activity during our ongoing pandemic.

You may have guessed by now that I enjoy being a little silly. It is my own personal way of classroom management: keep students guessing if I really am as kooky as I present (probably yes). If I have to choose between being a cop (which a lot of teachers enjoy cosplaying as) or a weirdo, it will always be the weirdo for me, hands down, no contest. If it does not feel natural to you, don’t do it: being a hardass does not come naturally to me, so I do not even try, and my teaching has benefitted. Being unusually whimsical does come naturally and as an introvert, I lean into this Frizzle-esque teaching persona (extension of self, really) that allows me to keep students engaged.6

So, just when students think it is back to business as usual, I walk into the classroom with about 6 or 7 different tote bags (exact number determined by how many students are in the class), filled with random items. I tell them that on the bus this morning, I decided to do some light theft. But now, I am racked with remorse and need to find the people these bags belong to: it is now their responsibility in small groups (again, ideally, 3-5 students and different groups than those who did the murder mystery activity together) to determine who owns each bag.

Their goal as a group is to create a character profile using specific details from what they find in the bag. Once again, whatever claim they make (what kind of person owns the bag) must be backed up with specific evidence (the items in the bag and the bag itself) and an explanation of how that evidence leads to their claim (ahem, analysis!).

Of course, I have not actually stolen these bags on public transit, but have spent the night (the weekend) before rounding up random tote bags at my place and placing an assortment of tchotchke in each one. I do take some time to create my own personal character profile for each bag, but it really could be as delightfully random as you would like it. I first encountered this activity at a summer camp when I was 15 and I enjoyed it so much that 10 years later as a student teacher, I turned it into one of my foundational close-reading lessons.

After the groups have their bags, I give each group a handout with the following information:

What’s In the Bag?

For each item in the bag, do an up-down-why.

Is the item something positive, something you feel good about, happy, etc? Why?

Is the item negative, something you feel bad about, sad, etc? Why?

Look for patterns and meanings behind those patterns.

Repetitions

Are there multiples of any item?

Multiples of any type of item?

Contradictions

Are there items that contradict each other?

Is there an item that is not like the others?

Similarities

Are there connections between items?

Are there items that seem to belong together?

What do we know about this person based on what’s in their bag?

What don’t we know about this person based on what’s in their bag?

Why do you think this person would need a bag like this and why the particular items in this bag?

I also use this as an opportunity for explicit instruction of academic language. Especially as someone who has taught English language learners—and is always thinking of all of us as lifelong English language learners—I find sentence frames to be valuable and particularly so when teaching new skills. If you are teaching 9th or 10th graders, keep in mind that the leap from summary to analysis is likely a new skill for many of your students.

I think that students need to learn not only how to analyze—the goal of this activity—but also how to use the language of analysis, and it is our responsibility as teachers to model this directly. Sentence frames are one effective method of doing this. If you find sentence frames creativity-stifling, make sure to include a wide variety of options and ultimately, to use them as language building blocks that students can build with, but do not have to use in order to be “correct.” If students can write without them, that is great; that is the ultimate goal, that in practicing academic language, they will become fluent and original. To the above ends, I include the following on the back of the handout and ask students to use it in putting together their claims:

PHRASE & VERB BANK

In presenting to your classmates, use the following phrases to help explain how you are using the items as evidence:

suggests a mood of

strikes us with the sense that

invites/prompts/moves us to feel/imagine

focuses our attention on

creates a mood/idea of

reveals/illustrates/conveys

depicts/shows/demonstrates

For example:

The gothic novel reveals that this person likely enjoys scary stories and along with the copy of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven,” this suggests a mood of eeriness. The DVD of the sitcom Schitt’s Creek, however, invites us to imagine that this person has a sense of humor as well.

The goal is for students to use patterns and their evaluations of those patterns to create an evidence-backed claim. And again, that is what we do when we analyze poetry: we look at patterns and we look at what those patterns indicate. We are not trying to “get” the poem: we are walking around in a poem and noticing. Close-reading is the flashlight pointing out what otherwise might be in the dark.

This activity builds community between students as well and allows them to collaborate towards a common goal while strengthening their analytical skills. They know that they cannot simply describe the bag and what’s in it: they need to take that evidence and lead it towards a claim. While I’ll admit that nothing can top the murder mystery activity, this one is also a great deal of fun.

Once students have shared their claims about who owns the bags (and I’ve admitted that no theft has been committed, though to be clear, no one has ever bought that), I then explain how what they have done is to close-read a text.

Linking this to a poetry unit, you might explain now how the bag is the same as the form or container of a poem: how does a sestina set up expectations for us that are different from that of a sonnet? In the same way that a tie dye gym bag sets up different expectations for who owns it than a Trader Joe’s reusable tote does7. Different containers—forms—set up different goals, or if we must, "meanings."

This also then leads us to looking at what exists inside of a poem as what we might learn from the items within a bag and here, we look for specific patterns, specifically the following that I deliver to students in a separate handout (and a series of lessons ongoing throughout the school-year). I often first share this handout following this specific activity and I am including the entirety of it below. Once again, you are welcome to use and modify it as you would like for your classroom8:

THE LANGUAGE OF CLOSE-READING

Close-reading methods include:

Up-Down-Why (Connotations)

Repetitions

Similarities

Contradictions

Key Questions (Author’s Intent / Narrator’s Intent)

These are among the main ways to close-read, or to deeply analyze a text at the level of language beneath the initial surface-level reading. In order to do this, though, you need the language to make it happen. Think of the close-reading methods as the knitting pattern whereas the close-reading language is the needles and the text is the yarn. The pattern tells you how to knit (analyze) the yarn (the text), but you cannot get anything done without your knitting needles (the close-reading language).

Below you will find some non-exhaustive lists of close-reading sentence frames and phrases to use for each method of close-reading:

Up-Down-Why

This detail suggests a mood of . . .

This creates a mood of / an idea of . . .

This strikes us with a sense of . . .

Repetitions

A common pattern is ___________ and this reveals ________________.

In mirroring these images / themes / moments, the text illustrates ________________.

Similarities

A common thread is ___________ and this reveals ________________.

The parallels found here represent _______________.

Contradictions

In contrast, this moment depicts how ____________.

However, the pattern breaks when _______________, thus demonstrating ___________________.

Narrative & Authorial Intents

The narrator’s motives become apparent given that _________________________.

Given the author’s perspective, an analysis of this segment of the text conveys how _______________.

MODEL: “With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city of Omelas, bright-towered by the sea.”

Close-Reading Analysis: The “clamor of bells,” combined with the image of “swallows soaring” suggests a mood of joy and celebration. The “Festival of Summer” focuses my attention on this sense of celebration. Describing Omelas as “bright-towered” invites me to feel a sense of optimism. Showing Omelas “by the sea” depicts the town as beautiful and picturesque. The alliteration with the smooth sound of “s” asks me to view this society as soft and gentle, like the fluid sound I hear as I read.

If you’re guessing that this is not a one-and-done lesson, you are absolutely correct. We spend the whole year learning and re-learning this. This lesson is merely the introduction.

What is Up-Down-Why?

Something to note in particular is that I refer to connotations—or the feelings, “vibes” if you will, that we associate with a word—as “Up Down Why” because in the course where I learned how to teach this close-reading method, the professor (Sarah Levine) had us practice by putting our thumbs up or down upon seeing an image portrayed on screen. This is an easy and effective way to teach connotations: create a slideshow with different images; ask students to give a thumbs up for positive, down for negative, or sideways for mixed and then to explain their reasoning.

Then, explain the parallel between this and examining connotations in a literary text. Words with the same dictionary definition can evoke deeply different feelings. I give students the examples of “smell, scent, fragrance, and stench”: “smell” evokes mixed emotions—the smell of garbage versus the smell of fresh-baked cookies—whereas “scent” is neutral and almost clinical; “fragrance” immediately is positive whereas “stench” is negative.

Making these connections will naturally be harder for some students than others and I encourage frequent returns to discussing how connotations work, including giving students a chart with the key word on the left-most column and having students write synonyms (or near-synonyms) with positive or negative connotations. This can be especially helpful in teaching students tone, a valuable literary technique to understand not only for poems, but in general.

Author’s Intent / Narrator’s Intent

This definitely will likely require its own newsletter, but just briefly: I teach students very early on the difference between the author—the flesh-and-blood human who wrote what they’re reading—and the narrator—a literary device who tells the story or presents what we’re reading (the speaker, in poetry). Sometimes, the author and the narrator are one; often, they are deeply different entities and it is critical to teach high school students this difference because they often, in my experience, enter not knowing it.

If you believe that an author’s identity has no relevance to the interpretation of their work, then we are honestly speaking different languages. As discussed in an earlier newsletter, this denial of the author’s identity in relation to their work feels like a convenient ruse for mostly white, mostly male, and mostly straight writers to pretend that their work is somehow universal and that the rest of us are niche. I think it is ridiculous and harmful. An author’s lived experiences inevitably will affect what they put on the page and how we as readers are to interpret it. T. S. Eliot and his fanboys can cry about it.

However, it is essential that readers not conflate the narrator—the author’s device—as the identity of the author and it is an easy mistake for students new to literary analysis like this. Again, there is more that I want to say about this, but I will cut this short here, with promises to return to the idea in a later newsletter. The TL;DR is that I have students distinguish between author and narrator and in particular, to examine what the author chooses to include and not include, and the same for the narrator, in order to better understand a text.

How to Teach This Without Sharing Items & Virtually

In an ideal world, when my return to the in-person classroom happened, I would have had ample prep time to figure out how to make my tried-and-true lesson plans work while adhering to the COVID-19 guidelines. In the real world, I did not and so I did not implement this activity over the past two years. What I realize now, belatedly, is that there is an easy fix: take pictures, whether your own or off the internet, and create a page of a document as a “bag.” To allow students to analyze the “bag" as container, you could include a picture of it on the back of this handout or attached.

No, it is not as fun as having students pull a slinky, a passionfruit LaCroix, and a keychain from Wyoming out of a tote bag from a Quebec farmer’s market . . . however, it does prevent students from handling common items and while COVID-19 is mostly airborne, this is one added measure for safety.

Additionally, this lends itself easily to being a virtual activity. By creating documents to represent “the bags” of items, you can share the links with student groups, then have them go into breakout groups to discuss, and finally return to whole class video to present their claims. (Note to self: a whole other newsletter needs to happen on virtual teaching.)

Endnotes

The Common Core standards for this activity are the same as for the “Spill or Kill” activity (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1 & CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1). I have taught this lesson with 12th graders and with 9th graders, and again, it is not quite as fun as the murder mystery, but it is still a delightful and engaging activity that generates a lot of student buy-in. By the end of it, students are able to see a little more clearly how they already have the skills to close-read—it is not just an academic, literary skill; close-reading is how we perceive and understand the world. What we aim to do in English class is to learn how to do it well.

We are all close-readers. The goal, really, is to be “joyful scavenger hunters,” to borrow again the words of one of my former students. We read the world around us on a daily basis. Sometimes, we actively or subconsciously turn this sense of witness off. Poetry is about reentering this state of witness and reconnecting with our senses, and this, I believe, is our goal when we teach it. We teach students to notice and to ask questions, to seek patterns and listen to what’s being communicated by them.

It is my sincere hope that the above two lessons can be of help especially to teachers who are new to teaching literary analysis at the high school level. My later newsletters will make reference to the information in this one and thus, this is probably the longest newsletter I will ever write.

Wow, if you have read this the whole way through, thanks for being here. If you’ve just read it in excerpts, I’m also grateful for you: way to go; this was very long. Hey—please make sure to finish your tea before it’s cold.

What I’m Reading: this newsletter over & over to proofread for errors

What I’m Listening To: ABBA’s “Angel Eyes”

What I’m Watching: those Aurora Teagarden murder mystery movies on Hallmark have been playing in the background (fittingly) throughout my writing of today’s newsletter

What I’m Feeling: the soft comfort of a cozy armchair

What Boba Flavor I’m Currently Craving: none, but only because I had several ube mochi ice cream . . . nectar of the gods!

I’m not a huge fan of the word “management” in relation to working with students and more generally think of this as “community-building and expectation/boundary setting,” but that is a mouthful and I’m using it here at the start so that teachers will know exactly what I’m referencing. I think the common framing of the classroom as a business to be “managed” is both weird and more capitalist than I’d like. I also think it works for some teachers and I simply am not one of them.

I am not saying this as an offhand joke. As someone who has been in both cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy to take care of my own mental health, I wish more people would seek this as routine maintenance and especially folks who are in professions that require as much emotional intelligence as teaching does.

I am not making any money off of this newsletter, so if folks could refrain from suing me for sharing this resource that was freely shared with me, that would be greatly appreciated (I say this in jest, but the internet is an odd place). I would love to give credit to whoever created this, which not even a reverse image search has made possible. The closest I’ve found is a variation on this with a slightly different drawing and story, called “Slip or Trip” from a book called Crime Puzzlement by Lawrence Treat. I have never read the book and am sharing this resource I received as a handout from my graduate course, but from what I’ve seen of it, the book could be a great resource for other similar activities.

This activity is one that I have used for six years now with 9th and 10th grade students.

For activities which I have done with 9th and 10th graders, I’ll use the 9-10 grade ELA (English Language Arts) Common Core standards, though it is helpful to note there is significant crossover with the 11-12 CC standards. When discussing activities and lessons specifically for the 11-12 grade levels, though, I will use those specific standards.

I talk a lot about in this newsletter about keeping students engaged, but I want, in another newsletter, to talk about how you are not a failure if your students are not always alert or even awake. If a child is asleep in your class, my first piece of advice is to not take it personally and then, be curious not judgmental (as good old Walt Whitman wrote). What is happening in students’ lives outside of our classrooms affects their lives in the classroom and it is up to us to be as compassionate as we can. This doesn’t mean that your class becomes substitute nap-time, but when a child is disengaged or even sleeping, that is a conversation to have, not a punishment to be dealt. (A whole other newsletter about doing away with “punishment” altogether.)

To be fair, it does feel like the same person could—and likely would—own these, and that the person is me.

Teaching students “Up-Down-Why,” or connotations, comes directly from Sarah Levine, who was my professor at Stanford and as previously mentioned, she was awesome—a favorite because she was good at what she did and also cared about us as her students. The rest of the close-reading methods, particularly repetitions, similarities, and contradictions, are my elaboration of close-reading techniques discussed in “How to Do a Close Reading” by Patricia Kain for the Writing Center at Harvard University (linked here). I first created this handout of close-reading methods and language during my student-teaching year in 2015-2016 and have continued to revise it yearly ever since. It is the foundation for how I teach students close-reading of poetry in particular, though I find it helpful for other genres as well.